Notes on Fort Cumberland

Reference

in C&O Canal Companion:

Canal Guide Mile 184.5

|

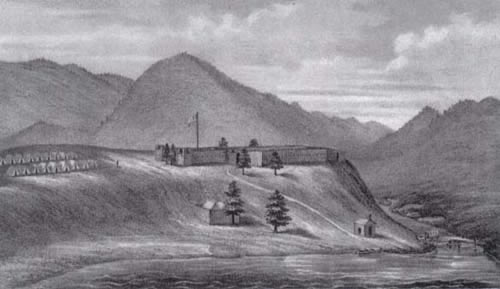

A

19th Century artist's impression of the

|

|

To be addedMile 184.5, Note for Cumberland: Governor Sharpe was less than impressed by the fortifications when he visited Wills Creek early in the winter of 1754 after Washington's defeat at Fort Necessity. He wrote to Governor Dinwiddie of Virginia on December 12 that he found the existing fort "exceedingly small" at about 120 feet across, and too easily approached from higher ground. Sharpe ordered the soldiers of the Maryland Company to build a larger fort on an "adjacent & more elevated piece of Ground," leaving the first structure as a "Store House or a Magazine." Next May, one of the British officers Braddock described the newly-christened Fort Cumberland: "[It] is situated within 200 yards of Will's Creek, on a hill and about 400 from the Potomack; its length from east to west is about 200 yards, and breadth 46 yards, and is built by logs driven into the ground, and about 12 feet above it." Eleven days later, he reported that 100 carpenters were at work building a magazine and constructing a bridge over Will's Creek. Despite the various improvements, Governor Sharpe reported to the Maryland Assembly next year that: "There are no works in this Province that deserves the name of Fortifications ... [Fort Cumberland] is at present Garrisoned by three Hundred Men from Virginia; it is made with Stoccadoes only and commanded almost on every side by circumjacent Hills..." The Lower House of the Assembly reminded the Governor of this dismissive statement later, when Sharpe sought funds to garrison the fort. Some members of the Assembly argued that the fort lay too far west of Maryland's western settlements to be of much use to that colony, and proposed instead that the colonies of Virginia and Pennsylvania contribute its support. Virginians had their own reasons for not liking the fort. In fact, far from serving as his headquarters, Fort Cumberland was a bit of a sore spot for George Washington. Captain Dagworthy of Maryland claimed authority over the fort, based on its location in Maryland and his seniority over Colonel Washington in length of service and by virtue of a royal commission he had once held. Dagworthy's claim rankled Washington no end, and while he pleaded his case with Governors Dinwiddie of Virginia, Sharpe of Maryland, and even Shirley of New York, he avoided the fort as if its garrison had the plague. Towards the end of 1756, Washington recommended that the fort be abandoned, but Dinwiddie demurred and insisted that Washington station himself there. It appears that Washington only spent a few weeks at Wills Creek before returning to Winchester and getting permission to go to Philadelphia, where the colonial governors were planning to meet with the new commander-in-chief, Lord Loudoun. At this conference, it was decided that Maryland would garrison Fort Cumberland, a transfer that was completed when Captain Dagworthy's company finally made its appearance on the first of May, 1757. For the better part of his service on the frontier, Washington's headquarters was to be at Fort Loudoun (present-day Winchester, Virginia).

|

|

Documents

George

Washington's sketch of Fort Cumberland, as reproduced in |

|

|

Further notes on Fort Cumberland: On a Sunday in June 1766, Charles Mason took a break from surveying the Maryland/Pennsylvania border and visited Fort Cumberland, noting in his diary for June 22:

|

|

|

Sources:

Also on the Web:

|