Saigon 1958 – 1964

One of the big events of our second tour was the attack on the presidential palace by two air force pilots on February 27, 1962. Ngô Đình Diệm and his brother Nhu made it to the bomb shelter unscathed, but Madame Nhu tumbled two floors down into a pile of rubble, sustaining deep lacerations and third-degree burns. The pilots succeeded in destroying one wing of the building, thus opening the way for the demolition of the aging French palace with all its memories of the colonial regime. It would be replaced by a brilliantly modern, very elegant “white house” designed by the distinguished architect, Ngô Viết Thụ.

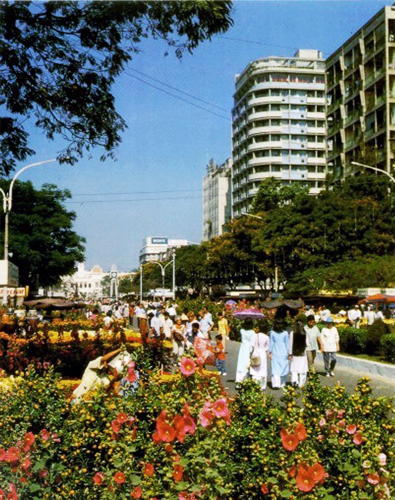

Nguyễn Huệ street, from the postcard that my mother received in 1958 alerting us that my father had found us an apartment.

From our balcony, I had a ringside view of the rush-hour maelstrom of bicycles and plucky little Renault taxicabs swirling through the junction where the broad current of Nguyễn Huệ was intersected by smaller tributaries. The Renault cabs—only slightly longer than a VW Beetle, with the engine in back, a blue body and a cream-colored top—were called “4CV,” which I understood to mean “quatre chevaux” (four horsepower). From my fifth floor perch, above the fray and even above the trees, I saw them dotted here and there, struggling heroically against the combined force of the bicycles, pedicabs (cyclos), and motor-cyclos.

(Left) Renault taxicab and a motorcyclo chase a lone bicyclist. Photo by Betsy High.

(Right) In the month before Tết, Nguyễn Huệ became a sprawling flower market. The government has since nationalized this business. (Unknown photographer)(Right)

Upon our return from our two-month “home leave,” we relocated to the second floor of small apartment building tucked away on tree-shaded Phùng Khắc Khoan. I had a vague idea that Khoan was a distinguished person, but it was only later that I would learn that he was a famous mandarin serving the Lê imperial line while they were in exile and after they were returned to the throne in in 1592. Being an eminent literati who was well-schooled in classical tradition, Khoan was selected as envoy to the Ming court, where he engaged in “brush talks” with like-minded scholars, including the Korean envoy Yi Sugwang. So, our second residence also had a bookish connection.

The Attack on the Presidential Palace, 1962

An aerial view of the Governor-General’s Palace (Palais Norodom), completed in 1872; renamed Independence Palace by Ngô Đình Diệm. The northwest wing of the building (to the right in photo) was destroyed in the 1962 attack.

Coming as it did from the sky, the attack gave almost everyone in Saigon an idea of the random terror and confusion associated with air strikes. The failed “paratrooper coup” of 1960 had played out in the streets right around the presidential palace, but this aerial display was something that everyone in the city experienced in one way or another. If my memory is not playing tricks on me, I was on the playground of the American School out near Tân Sơn Nhất airport, when I heard the chatter of machine guns and the droning of the propeller-driven planes. This was probably when the two rogue pilots strafed the airfield as they looped around to approach the Presidential Palace.

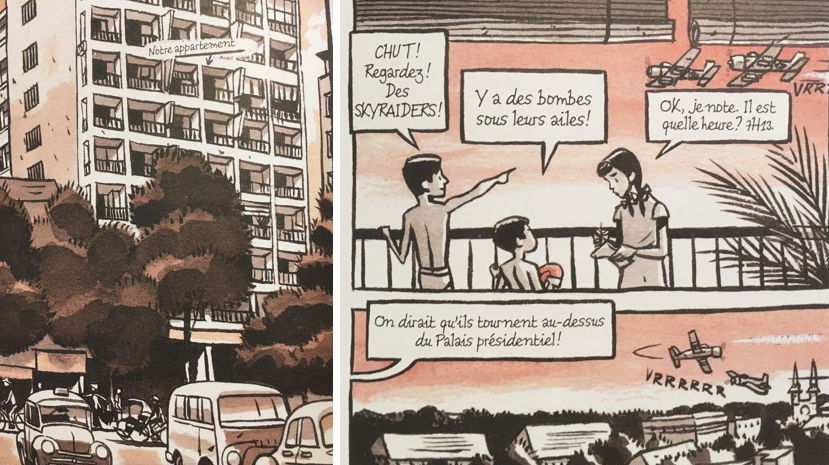

A few years ago, I came across a vivid depiction of the event in Marcelino Truong’s (literally) graphic memoir, Such A Lovely Little War. Marcelino’s family moved into the building on Nguyễn Huệ shortly after my family moved out, and, being a bit younger than me, was at home when the attack took place. Marcelino remembers the planes swooping right down Nguyễn Huệ as if the long boulevard was an arrow pointing to the Palace.

Marcelino Truong’s renderings of the building on Nguyễn Huệ (our apartment was on the fifth floor, one floor below his) and the air attack of February 1962.

The Trưng Sisters & Mme. Nhu

My photograph (on the left) and a color photo that appeared in the 1963 USO guide to the sights of Saigon. The Trưng sisters were national histories of the first rank, having led a rebellion against Han Chinese rule in 43 CE.

This was in April 1962, a month after the monument had been dedicated by Madame Nhu. Some were surprised that the de facto First Lady, was up and about so soon after the Palace bombing (two weeks earlier). But Diệm’s indomitable sister-in-law was in fine form, denouncing critics of his regime:

“Aside from the howling of the Communist wolves, we are really surprised to see a section of reputedly serious people of the free world continue to mouth certain sermons of pseudo-liberalism which indeed are insults to the democratic principles of free Vietnam.

Even now we continue to hear these various professors of democracy, unaware of reality, proclaim that the political and philosophical ideal of the Republic of Vietnam is not “attractive enough” to draw the masses of the people. According to them, communism and its lies are much more appealing to suffering populations.” (Reported by Homer Bigart in the New York Times, March 12, 1962 edition.)

This was relatively vague compared to Madame Nhu’s later diatribes against the western press, American officials, and Buddhist protestors, but it did provoke a private objection from the U.S. Embassy. (Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume II, Vietnam, 1962, Document 104)

In retrospect, I wish my nine-year-old self had gotten a close-up of the statues on the pedestal, because they were only on display for a year and a half. There was a public perception that the two Trưng sisters had been explicitly modeled on Madame Nhu and her daughter, and so they were taken as symbols of the state cult of Diệm. On November 2, 1963, the day after Diệm was overthrown, Ambassador Lodge reported in a cable:

At the big circle in which [stands] the statue of the Trung sisters which was modeled in the image of Madame Nhu, young men were busy with acetylene torches cutting the statues off at the feet and putting cables around the necks so as to topple them to the ground.

(Telegram From the Embassy in Vietnam to the Department of State, Foreign Relations of the United States, 1961–1963, Volume IV, Vietnam, August–December 1963, Document 270.)

The toppling of the statues was written up in the American press as a sign of the popular resentment of the regime (which was real enough), but the substantial preparation described in Lodge’s account suggests that the generals who had carried out the coup were also behind this demonstration.

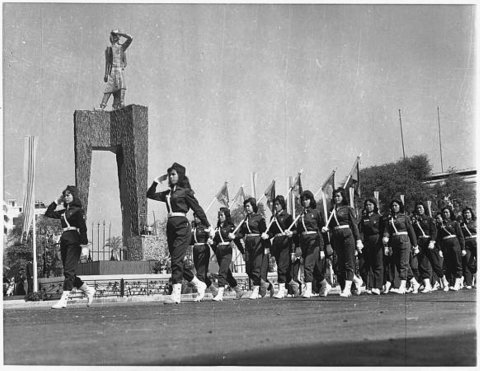

Revisionist historians have highlighted Madame Nhu’s efforts to organize women as a counter to the traditional view that she was no more than a flamboyant and erratic spokesperson for a dictatorial regime. There is truth in this, as Madame Nhu took dramatic steps to challenge the patriarchal conservatism that permeated the South Vietnamese government, including founding and supporting the Women’s Solidarity Movement. While her impeccably-attired paramilitary units were mostly for show—they would not face off against the “long-haired warriors” of the resistance in the countryside—they were a surprisingly progressive showpiece for a regime steeped in male prerogative.

My photograph (on the left) and a color photo that appeared in the 1963 USO guide to the sights of Saigon. The Trưng sisters were national histories of the first rank, having led a rebellion against Han Chinese rule in 43 CE.

Ugly Americans

The influential political novel The Ugly American had been published just before our transit to Saigon, and everyone in the American aid community knew about it. It was a full-on indictment of the American mission to reshape the world in its own image, without bothering to examine the facts on the ground. Part of the satire was directed against political careerists in the diplomatic service who were more interested in ribbon-cutting opportunities than long-term success. (This is, of course, a complaint that applies to every politicized bureaucracy, and there has never been a bureaucracy that was not politicized to some extent.) The exemplary heroes of the novel are the ones who get their hands dirty, who take the time to get to know the people on their home turf, and who pay attention to the situation on the ground.

In a 2009 essay in the New York Times, Michael Meyer reflected on the continuing relevance of The Ugly American (“Still ‘Ugly’ After All These Years,” July 10, 2009). On the subject of foreign aid in general, Meyer quotes one of Homer Atkins’ aphorisms: “Whenever you give a man something for nothing, the first person he comes to dislike is you.” Taken out of context, this sounds like Milton Friedman in a particularly bad mood, but Lederer and Burdick were really reformers, not anti-government absolutists. (In contrast, we have seen much more sweeping critiques of foreign aid in recent years, including Dambisa Moyo’s Dead Aid and The Great Escape by Angus Deaton.

Of course, no one in the American community wanted to be known as an “ugly American” (even if the unsightly character in the book was actually one of its role models). Accordingly, American families in the aid community received occasional newsletters encouraging respect for Vietnamese culture and explaining how we should comport ourselves in public. Of course, one was expected to bargain with shopkeepers, but it was not to be done in an insulting or excessively argumentative manner, as had been reported of some feckless teenagers. When anti-Diệm protests broke out, the newsletter called our attention to a Vietnamese saying about “bending with the wind” like the bamboo.

It was clear that we wanted to be different from the French, even if this was never said outright. The emphasis was on working on a basis of respect, trying to avoid an overbearing and paternalistic approach. In truth, Americans needed to do a lot to persuade the Vietnamese intelligentsia of their good intentions, given that the Americans had largely bankrolled the French colonial war from 1950-1954. News reports about racial segregation in America—much stricter than anything practiced by the French—were hardly reassuring. Could such a country really have the best interests of the Vietnamese at heart, or was America simply intent on establishing a post-colonial protectorate as a barricade against Communism?

On the other hand, many in Saigon were dismayed by the prospect of authoritarian Communism as practiced in the north, and were inclined to give the Americans a chance to establish themselves as something other than imperious westerners. One of these was Mrs. L. T. Bach Lan, who took the initiative to compile a lovely little book of classic Vietnamese tales in the year of our arrival. This was my first exposure to Vietnamese literature, and certain of the stories impressed me very deeply, none more so than the tale of Từ Thức and his time spent in the grotto of the fairy princess Giáng Hương. After what seemed like a hundred days, he became very homesick and went back to visit his former home, only to find that a full hundred years had elapsed. The idea of being a stranger in a strange land meant a lot to me, having been whisked around the world for the first ten years of my life. When I began writing short stories years later, I referred to Từ Thức’s tale and reimagined the scenario through the experience of my modern-day character.

American efforts to win the trust of their Vietnamese allies would end up failing dramatically at the highest levels of interaction. Diệm and his brother Nhu were always wary of American influence and they increasingly resented the pressure being applied by American officials pursue one policy program or another and to expand the regime’s base of support (e.g., to stop locking up noncommunist dissidents). But things worked out a little better when it came to immediate working relationships—as often is the case, informality and close contact tended to bring about accommodation, mutual respect, and occasionally even friendship

One thing that the newsletters could never explain, though, was the great mystery for Americans—how could so many well-educated Vietnamese in Saigon harbor sympathy for the resistance? In this case, Americans were at a particular disadvantage with respect to the French. France had a very large and active Communist Party, with substantial representation in the National Assembly, whereas Communism as a political force and even an academic theory had been almost completely eliminated in America. It was simply unthinkable, and thus we were unable to see the strong appeal that revolutionary Marxism had for many resistance leaders, who had seen their aspirations for self-rule repeatedly crushed by France’s democratic system, and had seen first-hand the expropriations of colonial capitalism.

The revolutionaries had little prospect of changing the minds of the “western imperialists”—especially given their crude and dogmatic messaging —but someone in Diệm’s Department of National Education evidently saw an opportunity to correct American stereotypes about their “underdeveloped” country. To that end the Department issued a series of English-language monographs in 1961. These included a short discursion on the Vietnamese language by Nguyễn Đình Hòa, a “regroupee” from the north who is best known for compiling an excellent Việt-English dictionary that is still available almost everywhere. (Hòa’s memoir of Hanoi also makes for excellent reading.) Similarly, there was an “Introduction to Vietnamese Poetry,” an “Introduction to Vietnamese Culture,” and an essay on “Democracy in Traditional Vietnamese Society.”

When I recently dug these brief summaries out of the family archives, I did not find any striking revelations, except for the fifth document in the series, “The Twain Did Meet: First Contacts Between Vietnam and the United States of America.” It included a sanitized version of Captain John White’s 1819 visit to Saigon and Edmund Roberts’ failed mission to Huế—stories well known to me—but also a remarkable account of an 1873 mission to Washington DC undertaken by Bủi Viện, a mandarin in the service of Tự Đức. In this account, Bủi Viện first went to Hong Kong, where he received a sympathetic hearing from the American consul, and then proceeded via Japan to San Francisco. From there, he presumably took the newly-opened (1869) trans-continental railroad route to Washington, DC, where, according to the story, he was able to meet President Grant, who seemed favorably disposed to his requests. However, on the way back, he was informed that “changed political circumstances would not permit the President to give the assistance that he had promised.”

I had not previously heard of this episode, and apparently for good reason—according to Wynn Wilcox, the trip is almost certainly fictitious. In his Allegories of the Vietnamese Past (2011), Wilcox traces the origin of the story to a romanticized biography of Bủi Viện by Phan Trần Chúc, published in 1945. There is no documentary evidence that would confirm Bủi Viện’s remarkable journey or his meeting with the President of the United States, yet the story was successfully promoted as an early contact between the countries, so much so that President Johnson was induced to offer a toast to Bủi Viện during his conference with Thiệu on Guam in March, 1967.

“Vietnamese Legends” Revisited

Bach Lan’s Vietnamese Legends was privately published, and the introduction gives no indication as to whether the work was supported by the Vietnamese American Foundation (directed by George F. Schultz at the time). But she must have been known to that group, as George F. Schultz credits her in the introduction to his own Vietnamese Legends, a larger collection published by Tuttle in 1965. The government publishing house, Thế Giới, reprinted Schultz’s work in the 1990s, without including his introduction or any reference to Schultz or those that he named as collaborators. (Thế Giới even went so far as to translate Schultz’s English back into Vietnamese in the subsequent bilingual edition, rather than going back to earlier Vietnamese sources.)

The bootlegging of Vietnamese Legends did not surprise me, since Vietnam does not have a tradition of copyright (Schultz’s book was published and copyrighted in Japan). For a long time I believed that I was possibly the only person in the world who had given this matter any thought, but recently I came across a very elegant essay by Harry Aveling that probes much further into the issues of translation and plagiarism with respect to Vietnamese Legends. Aveling gives primary credit for the modernization of Vietnamese legends to Phạm Duy Khiêm, one of the people that Schultz credited in his introduction for “aiding in the preparation of this collection.” (“The Shadow of the Absent Father: Pham Duy Khiem, Politics and Plagiarism,” in Translation Review, Volume 100, 2018.)

Khiêm was a French-educated intellectual who served as government ministerr and ambassador to France from 1954 to 1957 before disassociating himself from Ngô Đình Diệm’s regime. During the Second World War, he published his rendering of Vietnamese tales in Légends de les Terres Sereines (1942, expanded and republished in Paris in 1945). Given that Khiêm’s literary sources were ancient, his retellings could hardly be considered plagiarism, but Aveling nevertheless provides some interesting quotes that help explain why Vietnamese literati do not have quite the same attitudes towards creative ownership as westerners (at least, post-medieval westerners).

In using these old tales as the basis for his own writing, he was acting in accordance with what many consider to be the traditional Vietnamese approach to writing, which drew freely on the work of others and creatively reshaped it through the processes of editing, shortening, and developing. This was not considered plagiarism because, as Nguyen Nam notes, “originality [was] rarely regarded as a warrant of quality” up to this time. Furthermore, it was considered that “‘Imitation’ and ‘traditionality’ do not lead to the monotonous reproduction of pale copies of archetypal texts; instead they stimulate the evolution of texts that become more and more illuminated, rationalized or concretized on the basis of the same literary text.

Aveling sees a bit of “self-exotification” in Khiêm’s work, as he was adapting the tales to a French audience. That might be a bit harsh—Khiêm also pointed out similarities to no less exoticized European folktales, noting the resemblance of the story of Từ Thức’s sojourn in the fairy-grotto to the tales of Tannhäuser (German), Thomas the Rhymer (Scottish), and Niamh (Irish). (American readers would immediately think of Rip Van Winkle, but Khiêm may not have known about Washington Irving, or may have regarded his work as non-European.)

As for the English versions of these tales that were compiled by Bach Lan and George F. Schultz, Aveling finds them close enough to Khiêm’s versions to be considered plagiarism. (He cites a review by Nguyễn Khắc Kham that identified 14 of the 32 tales in Schultz’s book as having come from Khiêm’s work.) Presumably, this “borrowing” was known to Khiêm, as well as to other writers that Schultz mentions in his introduction. One of these, Lê Huy Hap, had published some of his own English translations of Vietnamese legends in 1963, with eleven of his fourteen tales taken from Khiêm’s French.

Schultz certainly could have done a better job in explicitly crediting those who “aided in the preparation of the collection,” at a minimum identifying whose translations were being used. Though it never pretended to be much more than an amateur project, it is very curious that Schultz presented himself as solely being responsible for the contents of the collection. But I am not sure that it was an example of self-aggrandizement and/or appropriation, which would have run counter to the spirit of the Vietnamese American Association. There are reasons why Schultz’s “collaborators” might have wanted to maintain a low profile in those turbulent times.

As for the Thế Giới edition, which gives credit to no one, it certainly deserves an introduction explaining that these are adaptations that are several removes from the original folk traditions. (Having been recorded from the vernacular several centuries ago, and subsequently translated into French, English, and quốc ngữ.) Better yet, it would be most helpful for Thế Giới to commission entirely new translations, directly from the oldest available sources of Vietnamese folk traditions.

PS. Aveling is no disinterested observer when it comes to translations of Vietnamese folktales. His article mentions Minh Tran Huy’s recent French adaptations, <>>La Princesse Et Le Pecheur and Le lac né en une nuit et autres légendes du Viêtnam, and he has translated Huy’s versions into English (Why the Sea Is Full of Salt and Other Vietnamese Folktales, 2017).

PS2. I probably should also call attention to the modernized versions of the classic Vietnamese tales by the eminent Buddhist teacher Thích Nhất Hạnh: The Dragon Prince., 2007 (previously published as A Taste of Earth, 1993). Thích Nhất Hạnh is very serious about his historical research, but when he wrote these tales (in Vietnamese) he was also concerned about the meaning they would impart to the children who heard them. So, the familiar tales have many reworked elements, and even a new character, Princess Sita.

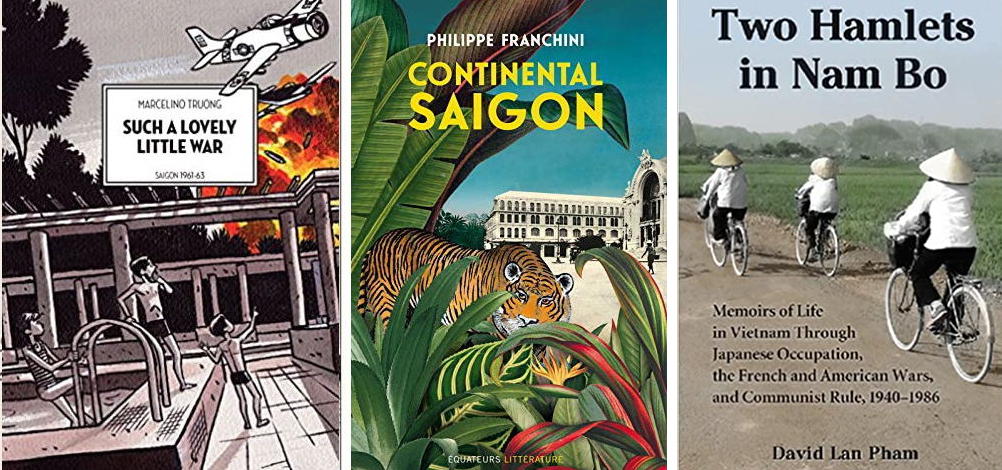

- Such A Lovely Little War, Marcelino Truong, published by Arsenal Pulp Press in 2016, is the English translation of Une Si Jolie Petite Guerre, 2012.

- Continental Saigon, Philippe Franchini, first published in 1976, republished 2015 (in French). Franchini’s father was Mathieu Franchini, a native of Corsica who purchased the Continental Hotel during the Great Depression (Philippe ran the hotel from 1965-1975). Philippe’s mother was the daughter of a Vietnamese official, and so he provides a mixed perspective on the colonial epicenter.

- Two Hamlets in Nam Bo: memoirs of life in Vietnam through Japanese occupation, the French and American wars, and communist rule, 1940-1986, David Lan Pham, McFarland, 2008. Pham was born in Thủ Dầu Một (just to the north of Saigon) and offers some telling vignettes about the wartime years in the big city.

- The experience of northerners relocating to the Saigon after the Geneva agreement of 1954 is recounted in two excellent family memoirs, The Sacred Willow: Four Generations in the Life of a Vietnamese Family, Mai Elliott and The Eaves of Heaven: A Life in Three Wars, Andrew X. Pham.

- Misalliance: Ngo Dinh Diem, the United States, and the Fate of South Vietnam, Edward Miller, Harvard University Press, 2013. The definitive scholarly treatment of the Diệm regime. For a different Palace perspective, see Finding the Dragon Lady: The Mystery of Vietnam's Madame Nhu, Monique Brinson Demery (PublicAffairs, 2013).

- Why Vietnam Matters: An Eyewitness Account of Lessons Not Learned, Rufus Phillips, Naval Institute Press, 2008. Over his fourteen years based in Saigon, Phillips wore many hats—Army officer, CIA case officer, USAID counterinsurgency official, and State Department consultant.

- My Father the Spy: An Investigative Memoir, John H. Richardson, Harper Perennial, 2006. One of the best-written memoirs of many by “American kids” in Saigon—no surprise, since Richardson is a top-shelf journalist and “writer-at-large.” His father was CIA station chief in 1962-1963.

- A Year in Saigon: How I Gave Up My Glitzy Job in Television to Have the Time of My Life Teaching Amerasian Kids in Vietnam, Katie Kelley. I mention this book because it is a rare glimpse of Saigon during the period when it was off-limits to most Americans. Katie Kelley first visited in 1988 and then decided to go back to Vietnam in 1990 to spend a year helping in a program to prepare Amerasian children of the war for emigration to the United States.