THANH HÓA – TÂY ĐÔ LAM KINH

Thanh Hóa, Jan. 2005 – After three more cycling tours of Vietnam (2000-2004), I had resolved to start traveling on my own account, developing itineraries of historical sites in different parts of Vietnam. I was very lucky to be get connected with a young historical researcher and editor who already had several notable publication projects to his credit. He liked the idea of traveling in this way, and so we set out together to tour the northernmost provinces. For the time being, I will simply call him Văn.

We headed south on our first trip, stopping at Hoa Lư to visit the temples to the first rulers of newly-independent Vietnam (10th century). The karst landscape is very picturesque, and it also afforded some protection from attack—in fact, the putative capital of the Đại Việt might be better characterized as a lair than a royal city. And yet, there was a trace of lordly elegance in the excavated stone floor of an old palace next to one of the temples.

From there, we drove further south to the city of Thanh Hóa, where we checked into the state-run hotel, which, unfortunately, had lost its electricity. Not really an unusual occurrence in my travels.

The Đông-Sơn Drums

We started the next day by dropping in on the staff at the provincial history museum. I don't know if they were officially open, but they graciously allowed us to tour the exhibits, which includes an extensive collection of the famous "Đông-sơn" drums. Many of these bronze-age instruments, with intricate designs on the drumhead, have been found in this province as well as in the Red River valley to the north.

Above: One of the Đông-sơn drums on display at the provincial history museum.

Below: A detail from the famous Ngọc Lũ drum, found to the southeast of Hanoi, gives tantalizing glimpses of deer, exotic birds, feathered warriors, and families living in stilt houses.

The name Đông-sơn simply means “East Mountain,” the place just northwest of the Thanh Hóa city where the drums were first excavated by archeologists. This is not necessarily the place where the drums were first made—other early examples of drums in this style are found in Yunnan province, now a part of southwestern China. Vietnamese and Chinese scholars have advanced competing claims about the drums: every Vietnamese scholar says that they originated in northern Vietnam, while every Chinese scholar says that the earliest drums are those found in southern China.

The term “Đông-sơn” is now applied to similar finds throughout Indochina and Thailand, places where they might have been traded as prestige goods before being produced locally. In the Vietnamese context, the drums are signs of the evolving Bronze Age culture along the Mã and Red rivers, neighboring but quite distinct regions.

Colonial Archeology in Thanh Hóa

The first excavations of the Đông-sơn site were carried out by Olov Janse in the 1930s. Janse has a remarkable biography: born in Sweden in 1892, he worked in France as a curator and lecturer, married Renee Sokolsky (a Polish émigré), and went to Indochina in 1934 to work with the École Française d’Extrême-Orient. Later, the Janses would move to America and become U.S. citizens.

In addition to the inland site at Đông-sơn, Janse undertook excavations at a site called Lạch Trường, evidently a trading port near where the Mã river poured into the sea. The discovery of burial tombs in the Chinese style, along with grave goods, suggest that ancient trading connections across the Tonkin Gulf linked this region to China as effectively as the provincial administration.

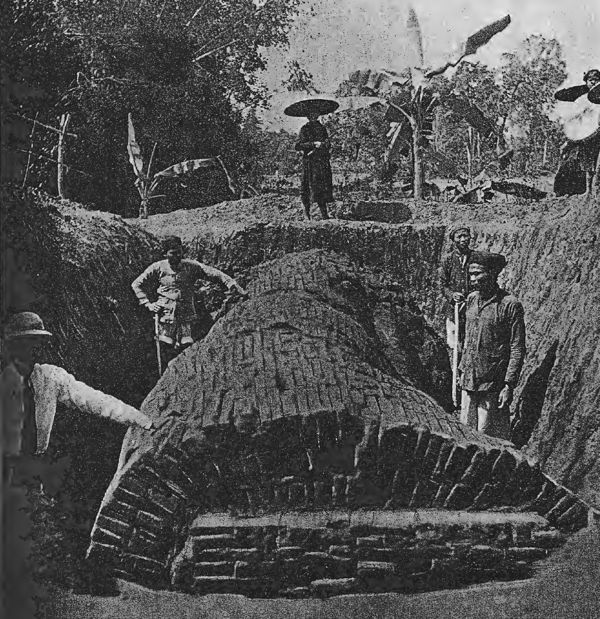

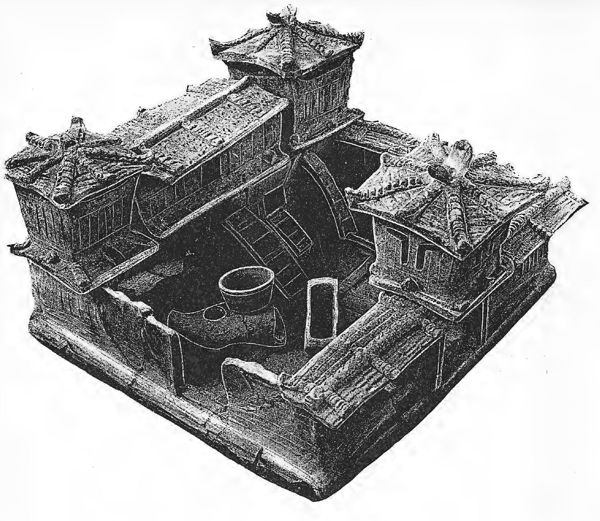

Above: excavation of a Han-style tomb near Lạch Trường.

Below: A model farmhouse, usually buried with the deceased, gives us an idea of how local leaders enclosed themselves in walled compounds.

The artifacts from the 1930s excavations were widely distributed in Europe, with pieces turned over to the Louvre, Guimet, and Cernuschi museums in Paris, the Museum of Art and History (Brussels), and the Museum of Far Eastern Antiquities (Stockholm). Some ended up in Peabody Museum in Cambridge, and other were given to private collectors; the few remaining items were given to l’École Française d’Extrême-Orient in Hanoi.

In an essay on the Peabody collection, Tawara Kanji speaks to the problems created when “artefacts recovered by a single archaeologist working in Viet Nam were dispersed into different collections located in many parts of the world with subsequent reports published in many different languages.” Others would go further in demanding that the foreign acquisitions of western museums should be returned to the countries of origin.

It is a complicated issue that should be examined with sensitivity. Certainly the Cham museum in Đà Nẵng ought to have one of the distinctive metallic lingakhosa that are currently only to be found in western collections. On the other hand, the countries of origin have not always acted as sympathetic guardians of minority cultures, and foreign collections have preserved much that would have otherwise been lost. As well, we might consider the reductio ad absurdum of a world where each museum only contained artifacts from the country where it is situated.

Hồ Quý Ly and the construction of Tây Đô citadel

In 1397, against the advice of several influential counselors, the powerful minister Hồ Quý Ly relocated the capital to this region from Thăng-long, calling it Tây-Đô, the "Western Capital." (As noted earlier, this is an odd designation, given its position just slightly west of Thăng Long.)

By 1400, Quý Ly had managed to graft himself into the Trần line of succession through the marriage of his son. However, his ambitious reform program was brought to a sudden end by the Ming emperor, who deposed him in 1407. During a 20-year occupation, the Ming garrisoned the citadel of Tây-Đô and used it as a regional fortress.

After Lê Lợi raised an insurrection in the upper regions of Thanh Hòa and drove the Ming forces out of Vietnam, he chose to make his capital in Thăng-long. However, the stone citadel in Thanh Hóa continued to figure in the national history as an important fortification in a province that was famous as the breeding-ground for rebellions. For example, an army was formed here in 1509 to overthrow an unpopular emperor in Thăng Long, and the citadel was the key point of contention during the insurrection of Lê partisans against the Mạc in the 1540s.

Having visited many historic sites that consisted only of rubble, my expectations were limited, especially after reading in a travel guide that nothing remained of the citadel but the southern gate (the most important of the four gates, which were oriented to the points of the compass). However, when Văn and I arrived, we were pleased to find that all four gates of the inner citadel were still standing, as well as the substantial stone wall that ran around the perimeter.

A buffalo cart exits the citadel through its three-portal southern entrance. Farmers have made good use of the interior, converting what were once palaces and promenades into rice fields.

Below: The warping stone wall next to the southern gate.

Aerial view: inside the walls, the royal city is now a mosaic of rice plots -- the pavilions, roofs, tiled courtyards, and dragon balustrades are known only through the descriptions in the chronicles. Presumably, any movable ornamentation was looted by the Ming and the wooden structures erected in later eras were probably cannabilized by the local population.

The East Gate (above) and the West Gate each consist of a single exposed arch.

2007 Update - I revisited the Tây-Đô citadel two years later to see if I could find the recent excavations of the "Nam Giao" platform where Hồ Quý Ly conducted the imperial "Heaven-Earth" worshipping ceremony. (The Đại Việt Sử Ký Toàn Thư entry for 1402 calls it a “tế giao” ceremony; the translator explains that this was performed at the winter and summer solstice; Hồ Quý Ly also conducted a “blood oath” ceremony at this place in 1399, before he had claimed the throne.) As it turned out, it was quite easy to find it by following the road from to the south of the citadel and asking people along the road for directions to “Đốn Sơn” (the mountain mentioned in the chronicles).

Of course, the remains of the platform were not as complete as the massive 19th century edifice in Huế, but the outline of the stone construction suggests the something quite different in the positioning of elemental forces. Notably, the geomantically significant mountain (actually a small hill) rises directly behind the worshipping platform, an important feature that is missing in Huế.

The excavations of the Tế Giao platform, with a processional path leading to an altar at the foot of Đốn Sơn.

The Vietnamese version of the Nam Giao ceremony practiced in Huế resembles those performed by the Chinese emperors—in Beijing, the equivalent platform is found next to the iconic "Temple of Heaven." However, the altar-platform in Thanh Hóa gives us a better idea of the older Vietnamese version of the ritual than the recently-unearthed remains of the Heaven-Earth platform in Hà Nội. Given that Thanh Hóa was adjacent to the Hindic Cham cultural zone, might the "heaven-communication" ceremony have been influenced by the devaraja ceremony practiced by the Khmer rulers? A ritual of communication with a central deity seems to have been an essential condition for kingship in the region--even the 18th century rulers of the city-state of Hà Tiên (on the coast of Vietnam near the Cambodian border) had their own Nam Giao platform.

2009 Update – By this time, I was making my trips with a fellow student of Vietnamese culture whose nickname is Nàng Ốc. In May, we revisited the Tây-Đô citadel and found that a small museum had been erected near the south gate. A charming museum guide wearing spectacles and an ao dai proved to be very well-informed about the history of the citadel and Hồ Quý Ly. I was impressed that the province had made an investment in the cultural site—this is quite rare outside of the largest cities. The reason became evident later, when we learned that a big push was on to have Tây Đô declared a World Heritage Site.

During this trip, Nàng Ốc and I were also able to find the fabled "Ly Cung" or "Banishment Palace" used for the luckless Trần emperor when the capital was moved to Thanh Hóa around 1397. At the time that he relocated the royal city, Hồ Quý Ly had not officially announced himself as emperor, but the nominal Trần emperor was a virtual prisoner, soon to be removed even further to a Taoist temple where he was quietly strangled. A small stele-house has been erected on the site, but the only remains of the Ly Cung were a few stones scattered amongst cattle browsing in a stubbly field. (A floor plan of the palace can be found in the History Museum in Hanoi.)

2010 update - Over the winter, an archeologist asked me to help with editing the nomination documents for "Hồ Citadel" to UNESCO seeking its registration as a World Heritage Site. The draft of this document made several interesting observations about the citadel site.

One was that the Tây-Đô citadel was the first to depart from a strict north-south orientation, for unspecified geomantic reasons. I was not sure what to make of this, since geomantic orientations often deviate from those dictated by the magnetic compass. In the case of Tây-Đô, the deviation is figuratively as well as literally a matter of "degree," being about like 25°. The former citadel at Thăng Long was also slightly off-line, though only about 5° from true north (according to my archeologist friend).

The most striking feature of the citadel is the use of massive blocks of stone for construction, on a scale not previously seen in Vietnam. The size of these stoneworks has ensured the citadel's preservation for all of these centuries. (During the same period, the citadel of Thăng Long went through several reconstructions and reductions, with the French finally razing most of it.) The nomination document includes intriguing description of the techniques used to transport the stone and erect the walls of the citadel, but the source of such techniques are still unclear. The nomination document suggests parallels with the stone edifices at Angkor in earlier centuries, but provides no evidence of direct transmission of these techniques to Vietnam.

As with Thăng Long and other capitals, Tây Đô citadel was surrounded by a much longer system of natural features and earthworks that enclosed villages and agricultural lands. Interestingly, the study reported that there is no evidence of a separate "Forbidden City" within the citadel, which is quite unusual. In Huế, for instance, there is a clear distinction between the sacred precinct (Tử Cấm thành) within the royal citadel, with the Queen Mother’s palace, the apartments of the concubines, and even the ancestral temples lying outside the emperor’s palaces. (The study did not make a direct comparison with the arrangement in Huế or Thăng Long.)

In considering the citadel’s design, the most immediate comparison—aside from Thăng Long—should be to the city walls of today’s Nanjing, which were constructed over the first two decades of the reign of the first Ming emperor (1368-1389). (He called this royal city, which might be interpreted as “In Accord With Heaven.”) Hồ Quý Ly was establishing himself at this time as the most influential minister serving the gradually weakening line of Trần emperors, and he would surely have been interested in the details of this vast project, which would likely have been relayed to him by the Vietnamese envoys who made frequent official trips to Yingtian, which was then the imperial capital of the "Central Effloresence" (Zhōnghuá, which is still a part of the official name of the People’s Republic of China).

As modern historians have stressed, Hồ Quý Ly’s rise and fall was part of a regional power struggle that pitted the “old guard” of the Red River region against the ascendant families from Thanh Hóa. While many of the great families of the along the Red River welcomed the Ming and worked for them, a powerful resistance movement emerged in 1418 in the upland area of Thanh Hóa. It was then that the great leader Lê Lợi "raised the banner of rebellion" in his homeland of Lam Sơn (Lam Mountain). In the course of the next ten years, Lê Lợi fought the Ming, was forced to submit to them, and then rebelled again, finally prevailing in 1427 and proclaiming a new dynasty.

The Royal Tombs of Lam Sơn

Lam Sơn was on our itinerary in 2005, as many of the tombs of the Le kings are still to be found there. In fact, according to the French scholar Louis Bezacier, 23 of the Le tombs were erected in Thanh-hoa; only 3 of the Le tombs were constructed in "Tonkin" (Hanoi region).

Driving to Lam Sơn gave a nice view of the "homeland" of the rebellion. The terrain was largely rolling hills, with many fields of sugar cane. Our first stop in Lam Sơn was the temple to Lê Lợi (referred to by his dynastic title of Lê Thái Tổ). A short walk from the temple, we came to the ruins that marked the site of "Lam Kinh" (Lam Citadel), the palaces used by the Lê kings when they came back to Lam Sơn to perform the ancestral rites.

All that remains of the Lam Kinh palace is the dragon balustrade and the bases of the columns arrayed in the field beyond.

Beyond the remains of the main palace, the path leads to the tomb of Lê Thái Tổ, the founder of the dynasty. The pillars and the wall enclosing the tomb appear to be of rather recent vintage, looking suspiciously similar to what one sees in Huế. The statues of the animals may or may not be copies, but if we take them as authentic representations of the older Lê style, they make an interesting comparison with those found at the Nguyễn tombs in Huế.

Where the Nguyễn have a series of mandarins flanked by a single horse and an elephant, the Lê had the rhinoceros, tiger, and lion, in addition to the horse and elephant, and only one mandarin in each row. We might take this as a reminder that upland Thanh Hóa was still a relatively wild place during the Lê period—Lê Lợi himself was described as having a fierce and wild aspect. In contrast, the rows of mandarins at the tombs in Huế suggest the rise of bureaucracy and formal civility over the ensuing centuries.

The tomb and large stele-house for the penultimate Lê king (Lê Hiển Tông, reigned 1740-1768) is also within this complex. He was one of the last figureheads of the “restored” Lê Dynasty; affairs of state were actually controlled by the Trịnh lords during this period. The last Lê emperor, Lê Chiêu Thống, disgraced himself by calling in a Qing army to return him to power in 1788.

Tomb hunting: the caretaker of Lam Kinh scans the sugarcane field for signs of the stele house below the tomb of Lê Túc Tông.

The tomb to the second king, Lê Thái Tông, is a bit further down the road, opposite the small hill known as "Núi Lam Sơn." It is has a stele house (though the stele has been removed from the back of the tortoise) and the traditional tomb courtyard with bestiary. At this point, things became a little more tricky, and we ended up going back to the crossroads of Lam Kinh and enlisted the help of the caretaker.

With his help we found most of the other sites around Lam Sơn, probably visiting 6 or 7 tombs in all, if you count the Queen Mother's tomb. As noted by Bezacier, only portions of some these sites are intact. The tomb of the 7th king was the furthest from the town, and finding the stele house proved to be a bit of an adventure, as it is entirely surrounded by a dense field of tall sugar cane. Bezacier's notes and map in the Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient (1947) indicate the remains of another 10 or so tombs further to the east along the Chu River, but we didn't have time to continue our search. There’s always something for next time ...

2010 update - When we next returned on September 28, 2010, it was happily on the occasion of a grand festival, the one held on the death-anniversary of Lê Lợi (22nd day of the eight lunar month). In older times, it is said, “Lowlanders and ethnic minorities use this occasion to bring to market honey, aloe wood, cinnamon, mushroom, cat's ear, herbs and other local products.” Now the temple and surrounding park land were crowded with families on an outing.

Festival goers present incense at the tomb of Lê Thái Tổ and relax on the platform of the stele-house (with one of the largest turtles in the country). The peccary-like creature next to the mandarin (first photo) is rather curious. Could it be a boar or perhaps a lion? Viet and Cham artists had no first-hand knowledge of lions and so their representations are sometimes quite fanciful. A copy of this creature is on display in the Hanoi museum.

- Vietnam, Ho Quy Ly, and the Ming, John K. Whitmore, Yale Center for International and Area Studies, Council on Southeast Asia Studies, New Haven, 1985. A close reading of Vietnamese and Chinese documents concerning Quy Ly's rise to power, the relocation of the capital to Thanh-hoa, and the Ming conquest.

- "Secondary Capitals of Dai Viet: Shifting Elite Power Bases," John K. Whitmore in Secondary Cities and Urban Networking in the Indian Ocean Realm, c. 1400-1900, edited by Kenneth R. Hall, Lexington Books, Lanham, Maryland, USA, 2008.

- Archaeological Research in Indo-China, Olov Janse.

Volume I, The District of Chiu-Chen during the Han Dynasty: general consideration and plates, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press 1947.

Volume II, The District of Chiu-Chen during the Han Dynasty: description and competitive study of the finds, Cambridge, Mass: Harvard University Press, 1951.

Volume III, The Ancient Dwelling site of Dong So’n (Thanh Hoa), Cambridge Mass: Harvard University Press, 1958. - Early Mainland Southeast Asia: From First Humans to Angkor, Charles Higham, River Books, 2014. The latest iteration of Higham’s comprehensive account of archeological research in Southeast Asia.

- “A Tale of Two Waterways: Integration in Vietnamese History and Thanh Hóa in Central Vietnam,” Li Tana, Journal of Vietnamese Studies, Vol.12, Issue 4, 2017.

- “Les sépultures royales de la dynastie des Lê Postérieurs (Hâu Lê),” Louis Bezacier, Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient, Volume 44, 1951.

- “Discovery of Ly Cung (Banishment Palace),” Tong Trung Tin and Pham Nhu Ho, in Vietnam Studies, 1990.

- Le Thanh Hoa: étude géographique d'une province annamite, Volumes 1-2, Charles Robequain, G. Van Oest, 1929. [I have not been able to track down this very rare item—apparently there are no copies in U.S. libraries—but there is an English-language edition from the 1970s, microfiche OCLC 2561785.]