|

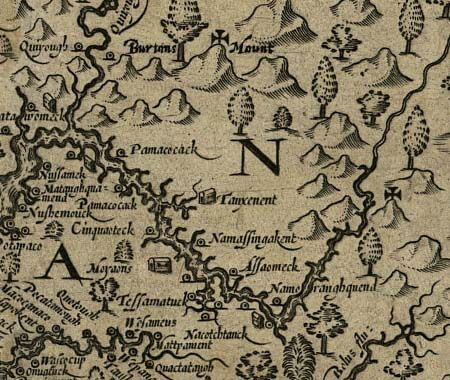

John Smith's map of his travels along the Virginia

coast and the Chesapeake Bay,

shows the furthest extent of his exploration up the Potomac.

According to the map legend, the cross denotes what he knew"by

discoverie,"

the rest of the map was based on what he learned "by relation."

The lower bend

of the Potomac in this detail is where the Potomac meets the Anacostia.

(Map

of Virginia 1624-Sixth State, Library of Congress American

Memory)

|

About

5 miles from the juncture with the Anacostia, Smith and his men

would have come to Little Falls, where the Potomac narrows

into a rapid torrent over an obstacle course of boulders.

At that point, Smith's vessel of "two to three tons burthen"

could have proceeded no further, though they might have

explored further on foot and by canoe. (Photo by M High)

|

|

Added

to Mile 4.5 in the Updated Edition:

From

the towpath you can follow a concrete-surfaced road down to the boulder-strewn

floodplain. At the end of the path, you?ll come to a concrete platform

with a good view of Little Falls. This is a good place to take a close

look at the impediment that likely ended John Smith's exploration up

the Potomac in 1608. The Army Corps of Engineers built the platform

in the 1970's as part of an auxiliary system to pump water up to the

Dalecarlia Reservoir in the event of a drought.

|

The

first description of Smith's trip up the Potomac appeared

in The Proceedings of the English Colonie in Virginia, 1612.

Though the book was Smith's, it attributed this account to

two

members of his party of fifteen, Walter Russell and Anas Todkill.

|

THE

PROCEEDINGS OF

THE ENGLISH COLONIE IN

Virginia since their first beginning from

England in the yeare of our Lord 1606,

till this present 1612, with all their

accidents that befell them in their

Journies and Discoveries.

From Chapter 5, "The accidents that happened

in the Discoverie of the bay"

|

|

****

3 or 4 daies wee expected wind and weather,

whose adverse extreamities added such discouragments to our discontents

as 3 or 4 fel extreame sicke, whose pittiful complaints caused us

to returne, leaving the bay some 10 miles broad at 9 or 10 fadome

water.

The 16 of June we fel with the river of Patawomecke:

feare being gon, and our men recovered, wee were all contented to

take some paines to knowe the name of this 9 mile broad river, we

could see no inhabitants for 30 myles saile; then we were conducted

by 2 Salvages up a little bayed creek toward Onawmament where all

the woods were laid with Ambuscadoes to the number of 3 to 400 Salvages,

but so strangely painted, grimed, and disguised, showting, yelling,

and crying, as we rather supposed them so many divels. They made many

bravadoes, but to appease their furie, our Captaine prepared with

a seeming willingness (as they) to encounter them, the grazing of

the bullets upon the river, with the ecco of the woods so amazed them,

as down went their bowes and arrowes; (and exchanging hostage) James

Watkins was sent 6 myles up the woods to their kings habitation; wee

were kindly used by these Salvages, of whome wee understood, they

were commanded to betray us, by Powhatans direction, and hee so directed

from the discontents of James towne. The like incounters we found

at Patawomeck, Cecocawone and divers other places, but at Moyaones,

Nacothtant and Taux, the people did their best to content us. The

cause of this discovery, was to search a gilstering mettal, the Salvages

told us they had from Patawomeck, (the which Newport assured that

he had tryed to hold halfe silver) also to search what furres, metals,

rivers, Rockes, nations, woods, fishings, fruits, victuals and other

commodities the land afforded, and whether the bay were endlesse,

or how farre it extended. The mine we found 9 or 10 myles up in the

country from the river but it proved of no value: Some Otters, Beavers,

Martins, Luswarts, and sables we found, and in diverse places that

abundance of fish lying so thicke with their heads above the water,

as for want of nets (our barge driving amongst them) we attempted

to catch them with a frying pan, but we found it a bad instrument

to catch fish with. Neither better fish more plenty or variety had

any of us ever seene, in any place swimming in the water, then in

the bay of Chesapeak, but they are not to be caught with frying-pans.

|

|

The

General History (1624)

In 1624, Smith published another account of his adventures as The

Generall Historie of Virginia, New England, and the Summer Isles.

Chapter Five "The Accidents that hapned in the Discovery of the Bay

of Chisapeack," used much of the material from the earlier work.

However, the following passage was added, giving more detail on the

point where Smith turned his boat around.

|

|

Having gone so high as we could with the bote, we met

divers Salvages in Canowes, well loaden with the flesh of Beares,

Deere, and other beasts, whereof we had part, here we found mighty

Rocks, growing in some places above the grownd as high as the shrubby

trees, and divers other solid quarries of divers tinctures; and divers

places where the waters had falne from the high mountaines they had

left a tinctured spangled skurfe, that made many bare places seeme

as guilded. Digging the growne above in the highest clifts of rocks,

we saw it was claie sand so mingled with the yeallow spangles as if

it had beene halfe pin-dust.

|

| Text:

This

transcription is found in The

Travels and Works of John Smith (Volume 1), edited by Edward Arbor

and A.G. Bradley.

A

more modern (and superbly annotated) presentation of Smith's works is

found in the three volume Complete Works of Captain John Smith,edited

by Philip Barbour, published in 1986 by the University of North Carolina

Press and the Institute for American History and Culture (Williamsburg,

Virginia). |