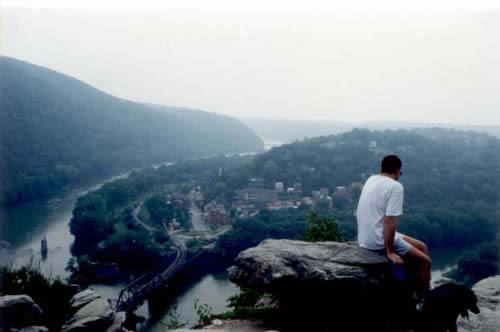

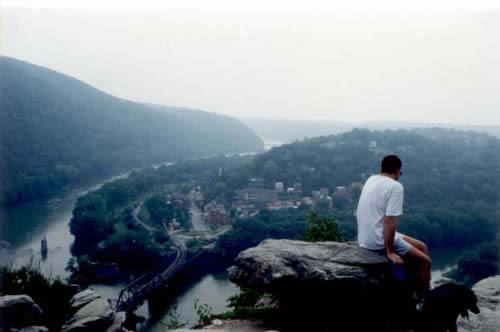

Worth

the hike: the cliffs of Maryland Heights give an exceptional

panorama of Harpers Ferry and the confluence of the Potomac

and Shenandoah Rivers, as well as a good idea of the

strategic advantage of the position. Loudoun Heights loom to the left.

(Photo by M High)

|

The

river lock had a peculiar feature, which led to a great embarassment

for Union General McClellan in February of 1862. As he sent General

Banks' division across the light pontoon bridge that his engineers

had finished just upstrem, McClellan was planning to set up a more

permanent bridge for reinforcements and heavy equipment, using canal

boats as pontoons. But when the canal boats arrived, the engineers

discovered that the river lock was narrower than the standard locks

on the C&O Canal, apparently because it was only intended to

transfer boats from the Shenandoah, which were built to smaller

dimensions. And as it turned out, the C&O boats were 6 inches

too wide to make it through the river lock. While McClellan still

had the pontoon bridge at his disposal, he was sufficiently disquieted

to call off his plans to proceed south to Winchester.

Lincoln

was furious at the delay, perhaps because he suspected that McClellan

was using it as an excuse for halting his forces, but he fixed his

anger on the failure to check the dimensions of the canal lock.

Since McClellan was not nearby, the President instead upbraided

his father-in-law: "Why in the Nation, General Marcy, couldn't

the General have known whether a boat would go through that lock

before spending a million dollars getting them there?" Wags

in Washington summed up the situation by saying that the expedition

had died of "lockjaw."

|

|

Mile

60.7:

Early

in the Civil War, both Union and Confederate commanders recognized

the importance of controlling the "Maryland Heights," that

portion of Elk Ridge that looms over the canal and the town of Harpers

Ferry. Abner Doubleday set about placing artillery here in the summer

of 1861, and a military road was constructed up the face of the mountain.

General Banks believed that "two or three pieces of heavy artillery

will command the town and sweep roads measurably all the roads leading

to it, as the turnpike to Charlestown, the road leading to Leesburg,

and the mountain road from Keys' Ferry to Loudoun Heights, and to

Harper's Ferry across the Shenandoah."

When

Colonel Dixon S. Miles rushed to the town of Harper's Ferry in September

1862 to command its defense, he was well aware of the importance of

the Heights, and ordered that it be defended at all costs. However,

shortly after the Confederates began their assault, Dixon ordered

a withdrawal, with the predictable consequence that the garrison in

Harpers Ferry was soon shelled into surrender. The quick surrender

made it possible for Stonewall Jackson to reinforce Robert E. Lee

just in time to stave off disaster at Antietam.

Colonel

Miles was one of the casualties, which spared him the fate of several

of his fellow officers who were arrested two weeks later and brought

before a military commission that had been assembled in Washington

to investigate this "unfortunate affair." The commission

collected a good deal of material that cast suspicion upon Miles'

judgment and even his loyalty, and concluded that the "strangely

unanimous testimony" demonstrated an "incapacity, amounting

almost to imbecility."

|

Documents

From

the Official

Records, Series 1, Volume 2:

HAGERSTOWN, Mn., June 23, 1861.

Col. E. D. TOWNSEND, Asst. Adjt. Gen. U. S. Army, Washington City:

COLONEL: Up to the present instant I have received from Capt. J.

Newton, Engineer Corps, only a report of a part of his reconnaissance

of the Maryland Heights and the ground adjacent, made in compliance

with the injunctions of the General-in-Chief. I hasten to give the

result thus far, expecting to-morrow evening to present the whole.

Captain Newton approached the heights from this side, ascending

over rough and steep roads difficult for artillery. The summit he

found capable of defense of ample character by about five hundred

men. The main difficulty to be overcome is the supply of water;

the springs, which a week since afforded an ample supply, have become

dry. He found no water within half a mile of the position selected

on the heights for an intrenched camp. In Pleasant Valley, on the

east, near the base of the mountain, springs are reported to abound;

their character will be ascertained to-morrow. Water would have

to be hauled from this valley, and he reports the ascent very difficult.

In this valley I propose to place the force sustaining that on the

heights. The whole command, if the location prove favorable, need

not exceed two thousand five hundred men. That force would render

the position safe; anything less would invite attack. *****

R. PATTERSON, Major-General, Commanding.

|

|

General

Walker's account of the bombardment of Harper's Ferry:

About an hour after my batteries opened fire, those of A.P. Hill

and Lawton followed suit, and near three o'clock those of McLaws.

But the range from Maryland Heights being too great, the fire of McLaws's

guns was ineffective, the shells bursting in mid-air, without reaching

the enemy. From my position on Loudoun Heights my guns had a plunging

fire on the Federal batteries, a thousand feet below, and did great

execution. By five o'clock our combined fire had silenced all the

opposing batteries, except one of two guns east of Bolivar Heights,

which kept up a plucky but feeble fire, until night put a stop to

the combat.

During the night of the 14th-15th, Major (afterwards brigadier-general

of artillery) R. Lindsay Walker, chief of artillery of A.P. Hill's

division, succeeded in crossing the Shenandoah with several batteries,

and placing them in such a position, on the slope of Loudoun Mountain

far below me, as to command the enemies works. McLaws got his batteries

into position nearer the enemy, and at daylight of the 15th the batteries

of our five divisions were pouring their fire on the doomed garrison.

The fire of my batteries, however, was at random, as the enemy's position

was entirely concealed by a dense fog, clinging to the sides of the

mountain, far below. But my artillerists trained their guns by the

previous day's experience and delivered their fire through the fog.

The Federal batteries promptly replied, and for more than an hour

maintained a spirited fire; but after that time it grew more and more

feeble, until about eight o'clock, when it ceased altogether, and

the garrison surrendered. Owing to the fog I was ignorant of what

had taken place, but surmising it, I soon ordered my batteries to

cease firing. Those of Lawton, however, continued someminutes later.

This happened, unfortunately, as Colonel Dixon S. Miles, the Federal

commander, was at this time mortally wounded by a fragment of shell

while waving a white flag in token of surrender.

|

|

Sources:

- George

B. McClellan, The Young Napoleon, Stephen W. Sears, Ticknor &

Fields, New York, 1988, reprinted by Da Capo Press, New York, 1999.

[See discussion of the problem with the river lock on pages 156-158]

- Six

Years of Hell, Harpers Ferry During the Civil War, Chester G.

Hearn, Louisiana State University Press, Baton Rouge, Louisiana, 1996.

- My

Life in the Old Army, The Reminiscences of Abner Doubleday, edited

by Joseph E. Chance, Texas Christian University Press, Ft. Worth,

Texas, 1998.

- War

of the Rebellion, A Compilation of the Official

Records of the Union and Confederate Armies, Series 1, Volume

19. [See Part 1, pages 550-803, for records of the Military Commission

on Harpers Ferry.].

- "Harper's

Ferry and Sharpsburg," by (General) John G. Walker, in The

Century Magazine, vol. 32, issue 2, June 1886, pp. 296-309. [Viewable

on-line as a part of Cornell University's Making

of America collection.]

|