The Second Chambersburg Raid

References

in C&O Canal Companion:

Historical Sketch, p. 36-37 and Canal Guide Miles 166.7 and 180.7

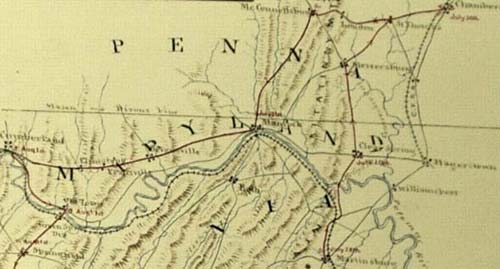

Detail

of map- photographed from the original in the Hotchkiss Collection, |

|

|

The red line on this map by Confederate cartographer Jed Hotchkiss shows the movements of McCausland and Johnson's cavalry: starting at Martinsburg, crossing the Potomac around Clear Spring, heading north to Chambersburg (upper right hand corner of detail), proceeding west and then south to Hancock, then west to Cumberland. The Confederates made it as far as Evitts Creek, where they were rebuffed by Union forces from Cumberland in the Battle of Folck's Mill. From there, the Confederates retreated along the Potomac to Oldtown, where they recrossed the river and proceeded south.

|

|

Documents

The following account by Confederate colonel Harry Gilmor gives a vivid picture of the desperate last full year of war on the Potomac (1864). This infamous raid is best known for the burning of the town of Chambersburg, Pennsylvania, but the experiences at Hancock, Cumberland, and Oldtown are full of interesting details on the Maryland residents and the river. Text from Four Years in the Saddle by Colonel Harry Gilmor, published 1866 by Harper & Brothers, New York. Photograph of Harry Gilmor from Library of Congress, American Memory collection. |

|

|

XLV. We left Chambersburg at noon, and went into camp McConnellsburg, where we found plenty of provender and rations. At length I got a good night's rest, and rose next morning much refreshed. General McCausland thought of sending Colonel Dunn and myself to Bedford Springs, but our rear guard being attacked, it was not thought prudent to separate the command; so we all moved clown the Valley toward Hancock, Md., which we reached about noon. General McCausland ordered a levy upon this place of $30,000, which was so out of all reason that we Marylander's remonstrated, but to no purpose. He told the principal men of the place that unless the money was paid he would burn the town. To this I and all my men objected, saying that too much Maryland blood had been shed in defense of the South for her towns to be laid under contribution or burned. I perceived, too, that his men were inclined to plunder. After a consultation with General Johnson, I brought in my whole command and stationed two men at each house and store for their protection. Before the money could be raised, Averill's troops arrived and attacked our pickets and outposts, and a lively little fight occurred, chiefly in the streets and on the high pine hills northeast of the town. My command constituted the rear guard, and did all the fighting in town, while a regiment and battalion of Virginians held the hills. About sunset we were ordered to retire and follow the column on the National Road toward Cumberland. While I was talking to some young ladies, the Misses B ?, before we left the town, a shell from the enemy came directly over the house, lodged on the bank of the canal, and killed two small boys. The ladies were excessively alarmed, and started for the house; but I called them back, assuring them there was no danger, and had partly succeeded in quieting them, when some carbineers opened a pretty sharp fire down the street we were in. The balls made a good deal of noise among the branches of a shadetree on the sidewalk. They all ran in, and stood at the door and window, imploring me to come in also. I liked to hear their pleading, and kept telling them, in the most indifferent manner, there was no danger, while, at the same time, had they not been there, I should most certainly have slipped behind the corner. But there I stood, and at the instant a ball struck my overcoat, rolled up and strapped behind my saddle, makillg a loud noise. My mare pranced, and the young ladies scrcamed. I felt a little uneasy myself, for I was a plain mark, and the range unpleasantly short; but, in a foolhardy fit, I resolved not to move unIess I or my horse was struck, or something turned up to give me a plausible excuse to be off. At last an orderly brought me an order from Johnson to retire, and, just as I was going, a ball struck my mare on the hip and gave her a bad wound. I had to ride her till midnight before I fell in with my black servant, who fortunately had my splendid black mare "Kitty," afterward taken by Major Young when he captured me the following winter. It is astonishing what perfect fools men will make of themselves when with these beauties. How you linger, fascinated by their winning way, when with a smile they beg you to "be careful," or "please don't expose yourself," or "please don't get wounded," not knowing, that their concern is the very thing to get a man into trouble. We continued our march on the National Turnpike until late in the forenoon of next day. McCausland's brigade had pushed on to Cumberland, where we found him engaged with General Kelly's forces, about two miles from that city. I saw at a glance that Kelly had the advantage, both in extent of line and position. General McCausland was sitting near a battery which was posted on a high hill, and doing good execution. When I reported to him he said, " Major Gilmor, do you know this country well ?" " No, sir, I was never here before." " Have you no guides ?" "I had two, but both got drunk and went off." "Unless we get out of this predicament soon, I fear it will be too late to save our guns and wagons, and we shall, besides, lose a good many men." He thcn asked me if I could not find a road to thc river by which hc could cross into Virginia, and at least save his ammunition wagons and artillery. I told him again I knew nothing of thc country, but I would take my command and make a recomloissance, if he so desired. To this hc readily assented, and I started of to hunt up a road. I cared not how soon we returned to Virginia. We had Kelly, with twice our force, in front in trenches; Averill coming up in our rear; the Potomac, seven or eight miles off, to thc left; the mountains of Pennsylvania on our right, with our commanders not on the best terms with each other. Such was our condition when, at 4 P.M., I set off to find a road. I had not gone more than half a mile before I obtained from a citizen all I wished to know, and, having dispatched this to the general, I seized a Union man as a guide, and started for Oldtown, on the Potomac. After going a mile or two, I sent back to inform the general as to thc condition of the road, and left pickets on the branch roads to guard us in flank until he should arrive and relieve them. The road was very narrow, and in one place led up the side of a mountain; but it was very firm. I had not gone more than three miles before it became dark night; but my guide, under thc persuasion of a cocked revolver at his ear, knew the country well, and made no mistake. About 1 A.M. we had reached to within a mile and a half of the river, the road leading along the side of a ridge, through a thick undergrowth of oak, pine, and laurel. I was riding with the advance guard, ahead of the column, sound asleep on my horse, when five or six shots were fired immediately in front, and, before I was fairly awake, another volley came from the right. I knew well what was up there, so, telling the boys to charge, and leading off myself with a yell, which, of course, they all responded to, we dashed on. Their bullets flew over our heads, and, although we could see nothing, we heard them retreating at a gallop. It was only n picket-post that must have been informcd of our approach, for they did not challenge. It was to answer the challenge that I rode with the advance, hoping to capture the picket and take possession of tbe bridge over the canal. It was not safe to advance farther in the dark, and without support; I therefore turned off into thc wood, planted an ambuscade for any thing that might approach, and sent sconts to explore the ford and give information. I sent a courier to hasten up Johnson, established vedettes, and then laid down to get some sleep. Daylight came, and with it our couriers, who reported eight hundred infantry and an iron-clad battery at the ford to dispute our crossing, and also a courier fiom Johnson, saying he would soon join me, so I started out on a reconnoissance. When I reached the canal I found they had burned the small bridge about a mile above Oldtown, but there was another of larger dimensions directly opposite the ford. A heavy fog enveloped the country for miles along the river and canal, and nothing could be seen. This caused my advance, under Kemp, to run into an ambuscade, by which he lost one man (Gorman) killed and two wounded. I deemed it prudent to dismount and wait for Johnson, who soon came up; and as the enemy in ambush had retired after giving us a volley, I went forward with two or three men to bring off the wounded, and see if Gorman was really dead. I found the poor fellow perfectly conscious, lying on his bacl;, shot in the abdomen by a Minie ball, which had torn a great hole, from which his entrails protruded. He was suffering intense pain, yet calm and rational, although he knew he had but an hour to livc. He told me his name was not Gorman, but Aristo. He joined us from a Louisiana regiment under a false name; told me not to waste time with him if I had any thing to do, and bade me good-by. His hand, as I pressed it, was then cold, and he died soon after. His comrades rollcd him up in his saddle-blanket, and buried him where he fell. When Johnson came up the mist had partially cleared away. We could see Oldtown, and a few Federal soldiers seemed to be taking up the bridge. Johnson thought we should make a dash for it, and went with me at the head of the column, his head-quarter flag in the rear, borne by a courier. There was a level stretch of road along the canal leading into town, and on the other side of the canal, between it and the river, a high ridge, partly cleared, and partly covered with trees and undergrowth. Not a man was to be seen, aud we started for town, but had not proceeded half a mile before a line of infantry opened upon us a rapid and continuous fire. The distance was about three hundred yards, but I presume they had fixed their sights for even a greater distance, as they often do, for not a man was hit, and but two or three horses. We were just opposite the mouth of a ravine. With one accord we left the road, ran up the ravine, and took shelter behind the hill.

|

|

|

XLVI. THE 1st Maryland had come no farther dovn than the bridge. Captain Welch went to work and built a new one, over which McCausland marched three regiments, dismounted them, and formed line of battle between the river and canal. Quite a lively fight ensued, but it resulted in the retreat of the enemy to the Virginia side of the river; where they took possession of a train of house-cars, wallcd up on the inside with heavy cross-ties for breast-works. There was an iron-clad battery, formed of rail-bars, at each end, with the locomotive in the centre. A large number of the enemy crowded into these cars, and the whole train was moved down the track directly opposite thc ford, within easy musket range of the bridge, and of the space betwecen the river and canal, and this was the only place on which we could place a gun to bear upon the train. One attempt was made to carry the ford with dismounted cavalry and my second battalion. We gained the river, and charged across under a heavy fire of shells and musketry, but could not go out on the other side. I drew up my squadron in single rank under the Virginia shore, in water knee-deep. The dismounted men waded through, and lay down on the edge of the water. There was but one way out, and that was up the steep hill where the road went forth from the river, under an enfilading fire from the batteries. Green Spring Run Station, on the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad, is exactly opposite. Besides the train there was a new block-house, built in the most approved style with bomb-proof, having one hundred men in it, commanded by Colonel Stowe, of Ohio. The block-house covered the ford at a distance of one hundred and fifty yards, with an open flat between, except just before the house, where the trees were. It must be acknowledged that our prospects were none of the brightest. We had lost about a dozen men in the fight, and yet gained nothing. I waited some time for McCausland to come to our aid, but, as he did not make his appearance, I went over to learn his movements and make some suggestions. I found him and Johnson in consultation; explained to them fully the position on the other side, telling them it was absolutely necessary to bring one or two pieces to bear upon the train and shell the infantry out of the cars. I described the country on thc Virginia side, which I knew well, and convinced them of the fact that Kelly was sure to bring down any number of troops from Cumberland when he found that we were checked at the river. They acknowlcdged the truth of my remarks, but said that artillerymen could not live under the musketry from the train, and that the horses would be killed before they could bring the guns into position. My horse had not been killed coming from the ford, and in the charge we had but fivc men killed; so, leaving them to their deliberations, I went back to Oldtown to see Lieutenant McNulty, of the Baltimore Light Artillery, and get him to take the almost desperate position. I found him, as I expected, ready for any thing. Accordingly, we took two pieces down to thc bridge; crossed it at a gallop; had two horses killed, which we dragged along dead in their harness; got a position on the ridge; unlimbered the pieces, already shotted and primed. The gunner was a Baltimorean named McElwee, and, though a brisk fire was opened on him, he coolly sighted his piece, and put a six-pound shell through the boiler, which exploded with a loud report. That was one of the best shots made during the war, judging from its effect, for every man except those in the iron-clad stampeded. The third or fourth shot entered the porthole of the iron-clad, dismounted the brass pivot-gun, whereupon both were evacuated. But the way was still not clear; for there stood the blook-house, really the greater obstacle, fiom the fact that it could not be seen from the Maryland sidc of the river: Lieutenant McNulty wasted about fifty shells feeling for it, only one of whicll pierced it through the roof. When the iron-clads were deserted, one of Johnson's Virginia regiments charged up the bank and received the fire from the block-house, by which it suffercd severely in officers and men. Thus matters continued for an hour and a half, McCausland and Johnson being unablc to decide on what course to pursue. We were all collected in a body under the Virginia shore, and if any one showed his head above the bank a bullet was sure to whistlc very near it. At length it was determined by McCausland to make a sudden and fierce assault, and the 8th and 21st Virginia were ordered to be put in position to make the attack. Just then it was suggested by some one to demand a surrender, notifying the commanding oflicer that, unless he complied, no quarter would be given after the place was taken. The two generals wondered that this had not been thought of before. Johnson wrote the message, which I sent by two of my men, Kidd and McCaul, one of whom was afterward in prison with me. They tied a white handkerchief to a cane, and advanced boldly to the block-house. The officer replied that his time was nearly out, and, if his men and of ficers were paroled, he would surrender. Most fortunate for us; it, no doubt, saved us many lives. I mounted my horse and rode forward to assist in forming the men, and soon after was ordered to scout the country and find out what had become of the escaped enemy. They had gone to Cumberland. After destroying the train we moved round to Springfield, nine miles on the Romney Road, camped two days to refresh our horses, and on the 3d of August went to Romney. Here all the wagons, dismounted men, and crippled horses were sent to the Valley. We marched out in the direction of New Creek, which McCausland had determined to capture, and which I believe would have been done had there been proper concert of action; but we spent two days uselessly, and were foiled most signally in that expedition, althougll McCausland did assault and capture one fort. We lost forty or fifty men, gaining nothing by the trip. Most of the regiments were demoralized, principally because of the amount of plunder they were allowed to carry.

|

|

|

Sources:

Also on the Web:

|